By Michael Guo, Molecular and Medical Microbiology ‘25

Author’s Note: After I returned home for winter break last year, I learned that a friend from my high school was diagnosed with testicular cancer. While I have limited experience with cancer and pathology, I hoped to educate myself about a topic that impacts and will continue to impact the life of one of my friends, and improve my medical literacy as well. This review is primarily based on discussing increased risk factors from testicular cancer and treatment, focusing on resulting secondary malignant neoplasms and cardiovascular disease.

Introduction:

In the past century, the two most prominent causes of death have been heart disease and cancer [1]. Heart disease disproportionately affects older adults, and cancer typically follows a similar pattern. One exception to this is testicular cancer, which in contrast to most types of cancer, occurs most often in 25-45 year old males [2, 3]. Another defining feature of testicular cancer is the extremely high survival rate in most patients, with most cases hovering around 95%. While this high survival rate is admirable, testicular cancer survivors have an increased risk for long-term effects and cancer recurrence from treatment compared to other cancers. Testicular cancer treatment greatly increases long-term effects from treatment compared to other cancer types treatments because survivors are often younger; the testes themselves are relatively exposed organs compared to the heart, lungs, etc, which makes cancer lumps more easily detectable, but also suggests younger survivors could live with long-term effects for multiple decades [4].

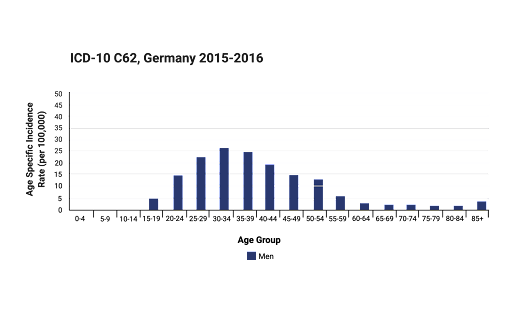

Caption: A study [10] depicts data collected on ages of TC patients, with a majority of survivors comprising the 25-45 year old age group.

Testicular cancer (TC), in its most simplified definition, is the uncontrolled division of cells (cancerous) in testicle tissues of males. Most treatments of TC consist of surgical removal of cancerous tissues, radiation therapy and chemotherapy, with the latter two encompassing more adverse effects. One such effect is the development of secondary malignant neoplasms (SMN), which are new cancerous cells that occur because of previous radiation therapy and/or chemotherapy [5].

The chemical drugs used in chemotherapy can also lead to various issues, including infertility, low testosterone, and various heart complications/diseases [6]. By deepening our understanding of the exact connections between TC treatments and their long-term effects, healthcare workers can greatly decrease mortality and improve the quality of life of testicular cancer survivors.

Testicular Cancer:

In order to distinguish when various TC treatments are utilized, there must be an understanding of the many forms and stages of TC. Testicular cancer almost always consists of germ cell tumors, which are cancerous cells that form from germ cells, or the sex cells (sperm in males). Non-germ cell tumor TCs are called stromal tumors; these are cancerous cells formed from supportive tissue in the testes, are relatively rare and can almost always be locally removed with surgery. There are two main types of TC germ cell tumors: seminomas and nonseminomas. Seminomas are localized in the testes and can be treated with surgery and subsequent radiation therapy and/or chemotherapy. Non-seminomas usually have spread throughout the body and require more intense chemotherapy, with subsequent surgery when needed depending on the stage/observations [7, 8]. These different forms of TC require different treatments; oftentimes patients receive a combination of multiple kinds. Most TC cases consist of germ cell tumors, have to be treated with some sort of radiotherapy/chemotherapy, and enclose many adverse, long-term side effects.

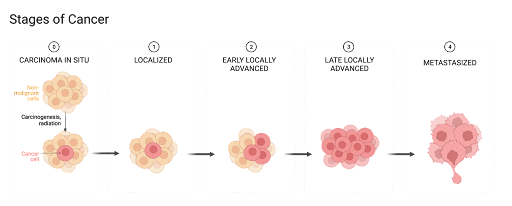

One of the most important designations in a cancer diagnosis is the stage. Cancerous tumors are categorized into five stages, with increasing severity from 0-4. Both Stage 0 and Stage 1indicate cancerous cells in one specific area, and are considered early stage cancers. Stage II and III are used when cancerous cells have expanded to surrounding tissues or the lymph nodes. Cancer cells that have spread are most commonly first found in lymph nodes, where developed cancerous cells can congregate from tissue circulation of the lymphatic system and spread to other organs. When cancerous cells spread past the original organ and lymph nodes, it is then classified as Stage IV, and is considered the most advanced stage of cancer [9].

Caption: Graphic showing the progression of cancer cell growth within a group of cells in the five cancer stages [7].

Statistically, most prognoses for TC patients are encouraging. A committee of German cancer statisticians observed that TCs only make up around 1.6% of cancers in men, and 90% of TC cases are diagnosed Stage I or II. On the other hand, TC also can also be categorized by various forms. Stromal or unknown non-germ cell tumors make up around 7% of all TC, while seminomas make up around 62%, and various non-seminomas around 31% [10]. Combined, the high diagnosis rate within early stages and the fact that the majority of cancer cases are localized result in close to a 95% 5-year survival rate, meaning a high number of patients survive for at least 5 years after diagnosis. Not to be overlooked however, is the impact of newly developed treatments of TC in the last 30 years.

Treatment and Side Effects:

Most of the adverse effects experienced from testicular cancer survivors are derived from the harsh treatment options available, rather than the cancer itself. So far, attempting to balance long-term effects from medication with sufficient treatment to remove the cancer cells has been proven to be the most successful course of medical care. All forms of TC can utilize surgical removal of tumors as a treatment option. When diagnosed early, surgery is almost always used to remove a testicle to prevent cancerous tissues from spreading. Surgical removal has little to no long-term side effects outside of normal surgical recovery standards.

More commonly seen with non-seminomas or more advanced stage TCs (stage III/stage IV) is the use of chemotherapy and radiation therapy. While chemotherapy uses specific drugs or drug combinations to target and kill rapidly dividing cells, radiation therapy uses focused radiation to break apart cancer cell DNA, which prevents division [8]. However, chemotherapy and radiation therapy come with different side effects. In chemotherapy of TC specifically, almost all treatments contain bleomycin, etoposide and cisplatin. This combination causes especially harsh long term side effects, including infertility, low testosterone, heart diseases and development of secondary cancers [2, 11]. In recent statistical studies tracking TC survivors who have undergone chemotherapy or radiation therapy (or a combination of both), researchers have noticed chemotherapy can increase the risk for SMNs and cardiovascular disease (CVD), while radiation therapy greatly increases the risk for SMNs but not necessarily CVD.

Caption: Graph visualization of cancer risk – blue line is depicting the risk of all cancers after a seminomatous TC diagnosis, compared to the green line representing general population risk of a seminomatous cancer. The red line depicts risk of all cancers after a non-seminomatous TC diagnosis, compared to the general population risk of non-seminomatous TC.

Secondary Malignant Neoplasms:

Healthcare professionals and researchers have long known that radiation and certain chemicals are able to cause cancer. Secondary malignant neoplasms (SMNs), as they have been termed, are when cancerous cells form outside of the original cancerous organ tissues, because of chemotherapy and/or radiation therapy. In a study published by Bokemeyer and Schmoll, research has suggested, “Radiotherapy is associated with a two- to threefold increased risk for secondary solid tumors” [4]. More recent studies have shown that patients exposed to higher amounts of radiation during treatment are more likely to develop SMNs than patients with lower amounts of exposure, since healthy tissues near cancer cells are exposed to high amounts of radiation at the time of treatment as well [4, 12]. Incidences of SMNs in TC survivors are especially noticeable and impactful; the younger age elicits more time for secondary cancers to occur post-treatment. While it seems that little can be done to combat the development of SMNs caused by radiation therapy during treatment, changes have been made in recent years. When doctors administer treatment of TC, if requiring radiation therapy, they aim to use minimal doses of radiation, and have completely stopped radiation therapy concentrated in the chest area in the past several years [13, 14]. While follow up appointments had been established before the long term effects of TC treatment have been quantified, follow up appointments are now taken more seriously and are being continued for a longer period of time following treatment, with a larger emphasis on secondary cancers.

Chemotherapy has also seen correlation with development of SMNs after initial treatment. Two of the drugs used in TC treatment, etoposide and cisplatin, have caused secondary malignancies to arise even in treatment of cancers other than TC. Researchers have come to agree that the impact of chemotherapy is less than radiation therapy in terms of development of SMNs. Decades old research has confirmed the correlation between complications following treatment and >4 cycles of cisplatin-based therapy [15]. Cisplatin in TC treatment has specifically been known to lead to increased risk of leukemia and myelodysplastic syndrome, both of which are related to complications to blood-forming cells in bone marrow. In another study, researchers equated the effects of chemotherapy and radiation therapy on SMNs and CVD to be similar to smoking, a well known carcinogen (cancer causing agent) [13, 14]. While the individual effects of both chemotherapy and radiation therapy regarding the development of SMNs have been documented, there have been few studies that differentiate the effects of each when both treatment options are combined. Future research surveying older survivors with more long-term effects could be the key to optimizing TC treatment when decreasing SMNs.

Cardiovascular Disease:

While both chemotherapy and radiation therapy have documented effects of SMNs, radiation therapy has not been connected to greater risk of CVD. However, among the various negative effects of chemotherapy, CVD has been one of the most important causes of premature death in TC survivors. In chemotherapy, cisplatin and bleomycin are heavy metals that with repetitive use, can build up in and weaken heart muscles, as well as cause hearing impairment and infertility [15, 16]. While the effects of bleomycin are similar to other heavy metals used in chemotherapy, cisplatin specifically damages mitochondrial or nuclear DNA of certain cells. This causes mammalian cells using ATP respiration in the mitochondria to create reactive oxygen species (ROS). ROS are unstable molecules formed from O2 that can then cause damage or cell death when reacted [17]. With repeated chemotherapy treatment, cisplatin can build up in certain areas, and is often the cause of side effects such as hearing loss (cochlea), hair loss (hair follicles), and CVD (inner linings of arteries). However, specifically why cisplatin builds up in certain tissues is currently unknown [11].

Cases of CVD from cancer treatment can especially be seen in TC because of the younger age of TC patients. Surviving TC at a mean age of 37 could mean living with an increased risk of CVD for upwards of 40 years. Researchers have attempted to substitute cisplatin with a similar compound called carboplatin in hopes of decreasing the known long-term effects. However, carboplatin has never produced efficient cure rates even while decreasing nerve and hearing damage [18, 15]. As stated before, it is unclear whether the long-term effects of cisplatin-based chemotherapy outweigh the monumental success rate of treatment of TC, simply because of the lack of data available from long-term survivors. Eventual data of TC survivors could help determine longer-term impacts of cisplatin in chemotherapy, and help with discussions regarding a need for finding a substitution for cisplatin.

Conclusion:

In regards to the post-diagnosis 5 year survival rate of testicular cancer patients, testicular cancer is one of the most survivable cancer types. However, the abnormally young age of TC patients allows us to more easily see the long-term effects of more advanced stage cancer treatment. Both radiation therapy and chemotherapy have been documented to increase risk for secondary malignant neoplasms, with chemotherapy also leading to a large variety of complications, including infertility, low testosterone, and cardiovascular diseases. While certain studies have shown such adverse effects in TC treatment, not enough data has been gathered from treated TC patients who have lived through a larger period of time since treatment. With future studies, researchers could discern the need for alternative treatments to testicular cancer, or methods to prevent the harmful effects of current testicular cancer treatment.

References:

- Leading Causes of Death. (2022, January 13). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/leading-causes-of-death

- Khan, O., & Protheroe, A. (2007). Testis Cancer. Postgraduate Medical Journal. Volume 83 (Issue: 984). https://doi.org/10.1136/pgmj.2007.057992

- Toni, L. D., ŠAbovic, I., Cosci, I., Ghezzi, M., Foresta, C., & Garolla, A. (2019). Testicular Cancer: Genes, Environment, Hormones. Frontiers in Endocrinology. https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2019.00408

- Bokemeyer, C., & Schmoll, H. J. (1995). Treatment of testicular cancer and the development of secondary malignancies. Journal of Clinical Oncology. Volume 13 (Issue: 1) https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.1995.13.1.283

- Virginia Cancer Institute. (n.d.). Secondary Malignancies. Retrieved March 7, 2022, from https://www.vacancer.com/diagnosis-and-treatment/side-effects-of-cancer/secondary-malignancies/

- Travis, L. B., Beard, C., Allan, J. M., Dahl, A. A., Feldman, D. R., Oldenburg, J., Daugaard, G., Kelly, J. L., Dolan, M. E., Hannigan, R., Constine, L. S., Oeffinger, K. C., Okunieff, P., Armstrong, G., Wiljer, D., Miller, R. C., Gietema, J. A., Leeuwen, F. E., Williams, J. P., . . . Fossa, S. D. (2010). Testicular Cancer Survivorship: Research Strategies and Recommendations. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. Volume 102 (Issue: 15). https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/djq216

- Johns Hopkins Medicine. (n.d.). Types of Testicular Cancer. Retrieved March 7, 2022, from https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/health/conditions-and-diseases/testicular-cancer/types-of-testicular-cancer

- The American Cancer Society medical and editorial content team. (2019, September 4). Treatment Options for Testicular Cancer, by Type and Stage. American Cancer Society. Retrieved March 7, 2022, from https://www.cancer.org/cancer/testicular-cancer/treating/by-stage.html

- Langmaid, S. (2016, November 28). Stages of Cancer. WebMD. Retrieved March 7, 2022, from https://www.webmd.com/cancer/cancer-stages

- Association of Population-based Cancer Registries in Germany & German Centre for Cancer Registry Data at the Robert Koch Institute. (2021, April 26). Testicular cancer. Zentrum Für Krebsregisterdaten. Retrieved March 7, 2022, from https://www.krebsdaten.de/Krebs/EN/Content/Cancer_sites/Testicular_cancer/testicular_cancer_node.html

- Murphy, M. P. (2009, January 1). How mitochondria produce reactive oxygen species. Biochemical Journal. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2605959/

- Curreri, S. A., Fung, C., & Beard, C. J. (2015). Secondary malignant neoplasms in testicular cancer survivors. Urologic Oncology: Seminars and Original Investigations. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.urolonc.2015.05.002

- The American Cancer Society medical and editorial content team. (2020, June 9). Second Cancers After Testicular Cancer. American Cancer Society. Retrieved March 7, 2022, from https://www.cancer.org/cancer/testicular-cancer/after-treatment/second-cancers.html

- van den Belt-Dusebout, A. W., de Wit, R., Gietema, J. A., Horenblas, S., Louwman, M. W. J., Ribot, J. G., Hoekstra, H. J., Ouwens, G. M., Aleman, B. M. P., & van Leeuwen, F. E. (2006). Treatment-specific risks of second malignancies and cardiovascular disease in 5-year survivors of testicular cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology. Volume 25 (Issue: 28) https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.2006.10.5296

- Moul, J. W., Robertson, J. E., George, S. L., Paulson, D. F., & Walther, P. J. (1989). Complications of Therapy for Testicular Cancer. The Journal of Urology. Volume 142 (Issue: 6) https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-5347(17)39135-8

- Travis, L. B., Fosså, S. D., Schonfeld, S. J., McMaster, M. L., Lynch, C. F., Storm, H., Hall, P., Holowaty, E., Andersen, A., Pukkala, E., Andersson, M., Kaijser, M., Gospodarowicz, M., Joensuu, T., Cohen, R. J., Boice, J. D., Dores, G. M., & Gilbert, E. S. (2005). Article Navigation Second Cancers Among 40 576 Testicular Cancer Patients: Focus on Long-term Survivors. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/dji278

- Breglio, A. M, et al. (2017, November 21). Cisplatin is retained in the cochlea indefinitely following chemotherapy. Nature Communications. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-017-01837-1?error=cookies_not_supported&code=95f5244f-996e-42ef-845e-9ca9f624b375

- Haugnes, H. S., Bosl, G. J., Boer, H., Gietema, J. A., Brydøy, M., Oldenburg, J., Dahl, A. A., Bremnes, R. M., & Fosså, S. D. (2012). Long-Term and Late Effects of Germ Cell Testicular Cancer Treatment and Implications for Follow-Up. Journal of Clinical Oncology. Volume 97 (Issue: 18) https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2012.43.4431

- Baird, D. C., Meyers, G. J., Darnall, C. R., & Hu, J. S. (2018). Testicular Cancer: Diagnosis and Treatment. American Family Physician. https://www.aafp.org/afp/2018/0215/p261.html

- Smith, A. (2019, December). The Long Haul: Facing the Long-Term Side Effects of Testicular Cancer. Cure Media. Retrieved March 7, 2022, from https://www.curetoday.com/view/the-long-haul-facing-the-long-term-side-effects-of-testicular-cancer