By Cristina Angelica Bilbao, Biological Sciences ‘22

Author’s Note: I performed this ethological research study for my Zoology class at Las Positas College. I love animals and was excited to have the opportunity to conduct research on an animal of my choice. I chose to research Canada Geese because I grew up around them and was initially scared of them. I wanted this project to be something that would help me understand the complex behavior of geese and provide knowledge to my community. I chose to go to Shadow Cliffs Lake in Pleasanton California because that is where a large population of Canada Geese live year round.

Above all, I hope this paper can convey that Canada Geese are not as aggressive as we may think. I hope that this paper can provide the knowledge that geese are actually a lot humans. With an understanding of their emotional displays, we can begin to understand them in ways similar to how we understand and interact with one another.

ABSTRACT

For centuries, biologists have tried to understand the mechanics of animal behavior. In 1963, Niko Tinbergen published four questions that allowed zoologists to focus on animal behavior in a scientifically rigorous manner. Tinbergen’s Four Questions center around four different concepts that could be related to animal behavior: Causation, Development, Adaptation, and Evolution.

In this ethological study, I aimed to explain if the neck raising behavior of Canada Geese was due to causation or adaptation. An adaptive behavior is a behavior that has been shaped by an environment over a long period of time, while causative behaviors can be linked to physiological responses to stimuli. I hypothesized that the neck raising behavior done by Canada Geese is an adaptation and not a causative behavior in response to a negative stimulus.

In order to understand this behavior, I observed a population of Canada Geese residing at Shadow Cliffs Lake in Pleasanton, California. Previous studies proposed that Canada Geese raise their necks due to an adaptation and not solely as a reaction to a negative stimulus. This study was done over a period of ten days with a close study and a distant observation study. If the distance was minimal, the geese were indifferent and only raised their necks out of curiosity. If the distance was further away with no external stimulus, the geese would still raise their necks at the same frequency. The results of this experiment was confirmed by concluding that the neck raising behavior of Canada Geese is an adaptation rather than just a reaction to a stimulus. I was also able to conclude that my observations were able to support the null hypothesis because the geese raised their necks at the same frequency during the close and distant studies.

INTRODUCTION

In the book Geese, Swans and Ducks [1], Canada Geese are described to be sociable and family oriented birds that show their emotions through a variety of displays.

Emotional responses can be the key to understanding Canada Geese behavior. It has been observed that dominance and aggression tend to be expressed simultaneously among Canada Geese. Bernd Heinrich, a professor of biology at University of Vermont, conducted an observational study on a breeding pair of Canada Geese. He made many personal accounts of how the breeding pair had a high intensity of aggression towards him while guarding their eggs. When Heinrich came back once their young had hatched, the pair was not aggressive and seemed to adjust to the researchers presence [2].

The prominent neck of the Canada Goose is an important indicator of emotional responses. Emotional displays characterized by head pumping, withdrawn necks, and vocalizations have been designated as situational and related to attacking or fleeing action [3]. The threat postures were categorized as having a variety of neck movements accompanied by vocalized hissing noises [4]. Another study was able to observe specific members of Canada Geese families taking up ‘guard positions’, which involved various sets of alert and alarm postures [3]. The alert and alarm postures were characterized with similar behaviors relating to threat postures. If the geese were in an alert posture, they would raise their necks high and freeze. If they were in alarm postures, the geese would more than likely begin to display similar threat behaviors of wing flapping and vocalization to warn the rest of the group. This behavior was seen equally between the male and female geese, especially at the time when they are protecting their nests from predators [3].

While it seemed that aggression was the only explanation for this reaction, I began to question if that was the sole conclusion that could be made. The Shadow Cliffs lake population usually could be seen on the beach, in the lake, or on the grass with minimal worry about threats. I observed that the geese lived mutually with the other waterfowl in the area and they seemed to have grown comfortable around humans due to constant contact. This could be one of the reasons that the group chose to stay in this area for prolonged periods of time.

Before I performed my observational study, I conducted two preliminary observations over two days and was able to notice an unusual behavior. At specific times of the day when the geese fed, members of the group would raise their necks at random. The neck extension would occur for about a minute before they went back to eating again. I believe that this may have been a form of communication, until I noticed another behavior that proved my initial hypothesis to be incorrect. While feeding, the geese would form a tactical perimeter around those who were eating in the center. The geese acting as guards on the outside would raise their necks for the longest periods of time and remain alert.

As I performed my preliminary research, I aimed to learn more about the population of Canada Geese residing at the lake. I interviewed Mark Berser, one of the Shadow Cliffs Park Rangers who has been working at the park for over 10 years. He confirmed the geese were usually around the lake throughout the year. He stated the tall grass by the water edge close to the picnic benches was a place the geese went to both eat and sleep. He had not observed the frequency of the geese’s neck raising behavior, but he was aware of the fact that they all seemed watchful in their close groups regardless of the threat.

I expanded my research to online scholarly journals, and I found more information regarding threat postures instead of the specific behavior I aimed to observe. These studies provided a generalized explanation on threat postures, which included neck raising [4]. I was able to find foraging studies that mentioned neck raising behavior as well, but it did not provide details about why the behavior occurred [4]. I was able to deduce that most researchers thought of this behavior as a biological reaction to a stimuli, also known as the attack-flee response [4]. The attack-flee response is a neurological response to a threat that prepares an animal to make the decision fight or to flee. I aim to challenge this idea by hypothesizing that the neck raising behavior done by Canada Geese is an adaptation and not a causative behavior in response to a negative stimulus.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Before I began my study, I gathered binoculars for observations and a field notebook to keep records of my observations. Next, I developed a detailed schedule relating to how and when I would observe the geese. I planned to conduct a ten day study on the population of Canada Geese in their habitat at Shadow Cliffs Lake. My observation days were on Mondays and Fridays before noon, in order to reduce the possibility of outside interference. If there was a situation that prevented me from not attending on Monday or Friday, I was able to make observations on another day at the same time in order to prevent discrepancies in the results.

During the first five days of the experiment, I positioned myself ten feet away from the geese. I casually sat at one of the tables in order not to disturb them in their normal routines. I then focused my observations on the frequency of the neck raising behavior over the course of one hour. Through these five days, I made sure to make note of the frequency of the behavior in my field notebook. Once the first five observation days were complete, the second portion of the experiment began. I made sure to arrive unnoticed as I positioned myself at a further distance away from the population. By keeping distance, I eliminated the possibility of the geese raising their necks as a reaction to my presence. During this time, I watched the geese with binoculars and took note of their neck raising behavior for one hour. I continued to take notes on the frequency of the behavior and I began to transfer the data to a table in order to properly visualize the results.

RESULTS

The target population of Canada Geese typically remained in a large group. On random occasions, smaller groups would split off from the rest of the family to either get an early start on bathing in the lake or to find food elsewhere. While they did split, they would eventually come back together in one location.

In large and small groups, there was a known presence of ‘guard’ geese. These geese would take position around the perimeter of the large or smaller groups. When the guard geese noticed me, they raised their necks more frequently and held the position for the longest period of time. The geese observed me before leaning down to eat and switch roles with another member.

During the first five days of observation, the geese were observed in close proximity. The geese were aware of my presence but they did not spread their wings or pump their necks in a threatened manner. Instead, they appeared to be indifferent towards me, raising their necks at a very low frequency as they waited to see if I had food. However, the geese would raise their necks more frequently if they felt that I was too close.

The second half of the observational study was performed at a further distance. The geese were unbothered as they continued with their usual daily routine. The guards and the others in the population raised their necks at low frequency, similar to what was observed in the first part of the study.

CONCLUSION AND DISCUSSION

In this ethological study, I aimed to observe the neck raising behavior of Canada Geese over the course of 10 days. During this observation period, I intended to explain whether or not the behavior was due to causation or an adaptation, as it relates to Tinbergen’s Four questions. Causation would describe the behavior as physiological while adaptation would describe the behavior as a reaction to stimuli developed over time. Through this study I was able to compare whether or not this behavior was more physiological or adaptive by taking certain factors such as visual stimuli and general environment into account. Initially, I hypothesized that the neck raising behavior done by Canada Geese is an adaptation and not solely a physiological response to a negative stimulus.

To successfully observe this behavior in the chosen target population, a variety of variables were taken into account. The Canada Geese were set to be observed without an external stimuli, which meant that time, presence of food and distance were all important variables. There was no food present and the population was observed at a time with minimal external stimuli exposure. The geese were observed from a far and close proximity in order to prove that neck raising behavior was an adaptation.

To support my hypothesis, observational data was collected over the course of ten days. Chart 1 presents the behavior observations from a short distance. The geese were aware of my presence because they raised their necks frequently, but they seemed indifferent towards me. More specifically, the perimeter guard geese seemed to be raising their necks the most and for the longest period of time. When the designated guards vocalized, the group of geese raised their necks collectively. I kept note of these results as I moved into the next phase of the study. Chart 2 depicts the behavioral observations made from a distance. Similarly, the geese raised their necks at the same frequency to look at their surroundings as they went about their daily routine.

The similarity in the results prove that the behavior of neck raising is not just linked to the presence of a stimulus. In relation to the work done by Blurton-Jones, neck raising and held erect posture could be perceived as a threat posture to drive away predators [8]. At a closer distance, the geese would raise their necks. While this could be seen as a threatened reaction, the behavior seemed to be more of an awareness of my presence rather than aggression. This was confirmed when the geese did not flex their wings or alert the group of a threat. The geese raised their necks and did not give any further reaction unless I got significantly closer. This allowed me to conclude that neck raising behavior is linked to threatening external stimuli.

With these results in mind, my hypothesis was confirmed. This experiment proves that neck raising behavior seems to be an adaptation developed through time as a method of protection rather than just a reaction to a stimulus. Through the act of raising their necks, the Canada geese make it known that they are aware of threats and are watching out for members of their family.

In the future, I would hope to perform more in-depth studies. Within my study, I was limited by the population of Canada Geese that I studied. The population of geese was the only significantly large population in Pleasanton, which ultimately limited my results. There was also a limiting factor relating to human contact; the group of geese that I observed had grown used to human contact instead of perceiving them as threats. While the group of geese displayed the behavior I aimed to observe, the results could be different in situations with limited human contact.

In future research, populations of Canada geese that have not experienced human influence should be observed. This would be able to prove whether or not the environment is a factor contributing to the neck raising behavior. Further research should include sexing the geese in order to rule out sex being a possible factor contributing to the frequency of neck raising behavior.

References

- Kear J. 2005. Canada goose (Branta canadensis).Ducks, geese and swans: general chapters, species accounts (Anhima to Salvadorina). New York (NY): Oxford University Press. P.306-316.

- Blurton-Jones NG.1960. Experiments on the causation of the threat postures of Canada geese. Wildfowl. 11(11): 46-52.

- Klopman RB. 1968. The agonistic behavior of the Canada goose (Branta canadensis canadensis): I. attack behavior. Behaviour. 30 (4): 287-319.

- Raveling DG. 1970. Dominance relationships and agonistic behavior of Canada geese in winter. Behaviour. 37(3/4):291-319.

- Hanson HC. 1953. Inter-family dominance in Canada geese. The Auk. 70(1):11-16.

- Herrmann D. 2016. Canada geese. Avian cognition: exploring the intelligence, behavior, and individuality of birds. Boca Raton (FL):CRC Press. P.72-143.

- Akesson TR, Raveling DG. 1982. Behaviors associated with season reproduction and long-term monogamy in Canada geese. The Condor. 84(2): 188-196.

- Heinrich B. 2010. Parenting in pairs. The nesting season: cuckoos, cuckolds, and the invention of monogamy. Cambridge (MA): Harvard University Press.p. 210-213.

Appendix

Chart 1: Field Notes Observation Table Results for Close Study

| Date | Day/Description | Summary of Behavior |

| 9/30/19 | Day 1- 1:30-2:30 p.m.

The weather at the time was comfortably warm. The sun was out and there was a light breeze. While it did seem like the perfect day to go out to the lake, there actually weren’t a lot of people in the area. This made it easier to reduce any interference. |

–In the large family of geese and even in the smaller sub groups, there were designated ‘guards’. These rotating guards seemed to have a strategy of holding the perimeter. They were the members of the group that actually raised their necks the longest and most frequently. They would hold their necks up for about 10-20 seconds.

-When it comes to noticing me or if I was too close, the guard geese signaled a call to the rest of the group. The call would get the rest of the group to raise their necks. Overall though, they didn’t seem threatened but instead either somewhere in between indifferent or curious about if I had food. |

| 10/4/19 | Day 2- 11:30-12:32 p.m.

The weather at the time was a little colder than the first observational day. The sun was out but it was all around a little colder with a slight breeze. There were not many people at the lake. |

–The entire family of geese would raise their necks at random points. It became clear that the ‘guards’ were in a position where the ones that had the most power to alert the group of any potential problems.

-The guards raised their necks the most frequently. -In an area with no remote threats, the geese still seemed to be very clearly aware of their surroundings. |

| 10/8/19 | Day 3-12:30-1:30 p.m.

The weather today easily symbolized that fall was near. The sun was out but it was cloudy and there was a strong wind. This ultimately made it a cold day. There were people but not many near the geese. |

–Similarly to the other two observation days, the geese were still mostly indifferent to my presence.

-If I got too close, the guard geese would make sure others knew about me, but they weren’t even close to being threatened. -The neck raising behavior occurred frequently when I was in the presence of the population. |

| 10/11/19 | Day 4-11:27-12:30 p.m.

The weather today was cold. I could still see the sun but there were more clouds than most of the other days. There also was a slight breeze. Once again there were not many people at the park. |

–The geese retained the same indifferent behavior towards me.

-Most of the time I could justify that they raised their necks simply because they wanted to be aware of me and maybe were hoping that I had food. -The guards at the same time still were the ones that raised their necks the most frequently. |

| 10/16/19 | Day 5-6:40-7:40 p.m.

Mainly because it was the evening, the sun was actually setting. The weather itself started to get windy and cold as the darkness approached. There were still a few people at the lake but they weren’t providing interference to the geese. |

–The geese were raising their necks every few minutes like usual and holding the position before they went back to eating.

-It was interesting to see that there were actually more guards around vocalizing and raising their necks quite frequently. -The guards were also still raising their necks quite frequently when it came to watching out for the small groups flying to the water to sleep. |

Chart 2: Field Notes Observation Table Results for Distance Study:

| Date | Day and Description | Summary of Behavior |

| 10/19/19 | Day 1- 1:20-2:20 p.m.

The weather at the time was sunny and warm. There weren’t too many people at the lake at this time, which minimized experimental interference. |

–The geese still seemed to display the same alert behavior through the action of neck raising.

-The perimeter guard geese still seemed to be the particular members of the family that raised their necks the most often and longest. The longest neck raised posture that the geese held was about 10 seconds. -The neck raising behavior would occur at random points of time to be alert of the surroundings and what the other members of the population were doing. |

| 10/22/19 | Day 2- 2:13-3:30 p.m.

The weather was sunny and warm, but there was a stronger breeze than the previous observation day. There were a bit more people at the lake today, but they weren’t anywhere near the geese population |

–The guard geese were still on alert both on the beach and in the park area.

– It is important to note that while the guards were the ones still raising their necks the most and the longest, the rest of the family was also doing the action. -When the guards seemed to vocalize, they had the power to get the whole group to stop eating and raise their necks to attention. The behavior also seemed to occur if two groups were calling to each other from two different locations. |

| 10/25/19 | Day 3- 1:13:2-13 p.m.

The sun was out but it was a bit colder, hinting at the arrival of the fall season. There were people fishing but since the geese took particular interest in feeding within an enclosed area, observation was not affected. |

–The geese in the parking lot and picnic area actually seemed to have similar frequencies of neck raising behavior.

-In the picnic area, the geese seemed extremely indifferent to the people in the distance and actually laid down. It was interesting to see the guards lay down as well, yet still raise their necks in the same frequency. -In regards to the group in the parking lot, it seemed that the neck raising behavior still occurred at the same frequency. The difference was more observable in how long the posture was held, which came out to be about 30 seconds. |

| 11/8/19 | Day 4- 11:30 a.m. -12:30 p.m.

There were a bit more clouds and a stronger breeze, but I could still clearly see the sun. The observations were carried out with no interference. |

– The guard geese prominently were still the usual members of the population raising their necks the longest and most frequently compared to the rest of the population.

-The geese that took up the roles as the guards happened to be the most alert and aware of the surroundings and other members of the family. – The neck raising behavior almost seemed summed as both a reaction to family calls and a general adaptation to watch the surroundings for any threats to the population. |

| 11/15/19 | Day 5- 12:40-1:40 p.m.

The sun was out but the overall weather was cold, mainly due to the strong breeze. Once again there weren’t many people around, which allowed for the geese to not get distracted. |

–On the final day of observation, the geese were in a much larger group feeding in the park area. There was also a small group on the beach.

-It was clear that there were designated guards, which told me that these roles were not just temporary. -The whole family would raise their necks, but it was the guards that raised their necks most frequently. -It seemed that the neck raising behavior was occuring quite randomly. Realistically this could mean that the geese raising their necks could be an adaptation to be aware of what the family is doing. It could also be an adaptation to avoid predators. |

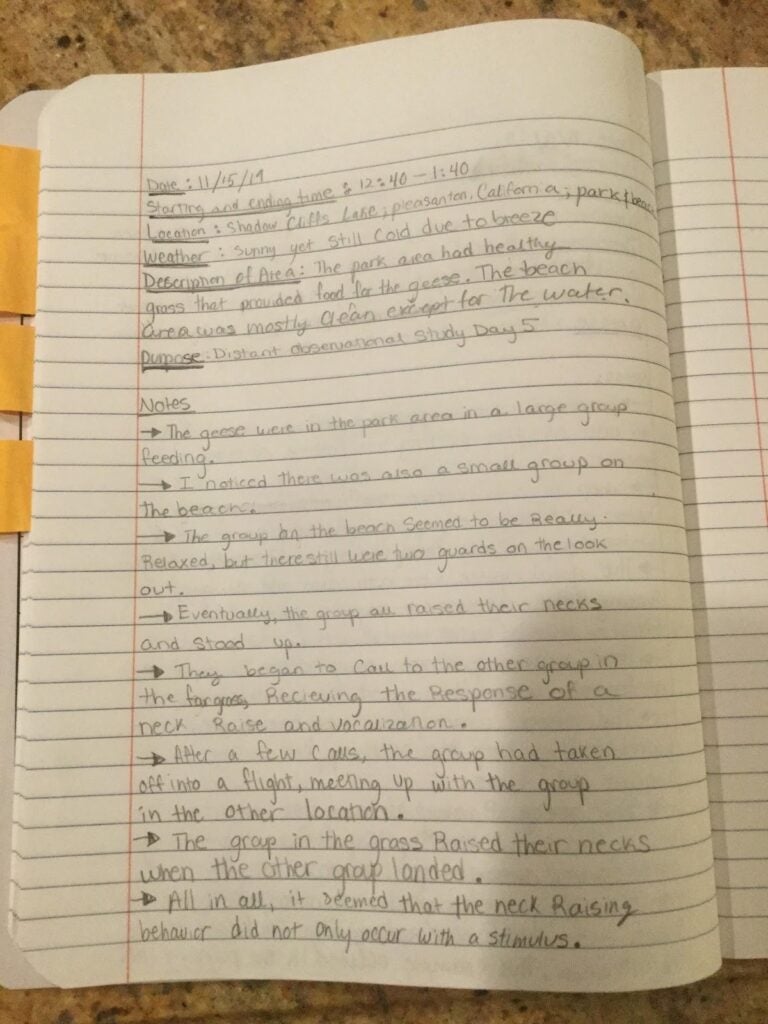

Field Note Photos and Supplementary Images:

- The first set of images are entries from my field journal. Though they may be difficult to see, the data has been summarized in the tables above.

- The second set of images depicts two instances where the geese were displaying neck raising action. They also show the guard geese in place.

Image 1: This image was taken at the time the close distance observations were being conducted. In this image, a group of geese can be seen eating on the grass of the park hill. On the far corners of the image, two guard geese can be seen taking up perimeter positions around the rest of the group.

Image 2: This image was taken at the time close observations were being conducted for the experiment. In this image, two Canada Geese, possibly a mating pair, were foraging in the grass. The current acting guard can be seen on the left.