By Jeffrey Nguyen, Animal Biology, ‘19

Author’s Note: I originally wrote this piece for UWP 104E: Writing in the Sciences. The assignment called for an explanation of any scientific topic to the general public and I thought to write on a topic that would be both useful and relatable to pet owners. Skin allergies affect dogs of all breeds and can bear severe consequences if left untreated. I hope that this paper increases awareness on animal health and convinces pet owners to consider taking a second glance in those moments they observe something out of the ordinary.

Over the summer breaks, I intern at the local veterinary hospital in my hometown. This hospital only takes patients on a walk-in basis, so the types of cases we see range from menial ones, such as nail trims, to full-blown emergencies, like animals hit by cars. It is almost impossible to predict the cases seen day to day. However, in this fast-paced, dynamic environment, there is one case that appears without fail: an itchy dog. At the hospital, I regularly shadow the head veterinarian, Mark Malo. Whenever a dog comes in with itchy skin, he usually gives the same spiel to owners: “When humans get allergies, they get a runny nose and watery eyes – hay feverish symptoms. When a dog gets allergies, it shows up as itchy skin.” His usual spiel made me realize that many dog owners are not aware of the potential for a simple itch to escalate into full-blown, infected hot spots. Often, owners would bring their dog in when its skin condition had already progressed to a severe state. Educating owners on common skin allergies may serve to stall disease progression if they notice clinical signs early. This initiative can reduce instances of disease progression and greatly improve the animal’s quality of life. This review will delve into common skin allergies in dogs and offer information on common symptoms and treatment options.

Occasional scratching is completely normal, but when it becomes apparent that the dog is chronically itchy or its skin is red and inflamed, one should consider a trip to a veterinarian. In veterinary medicine, chronic itches and skin-reddening are known as dermatitis and erythema, respectively. When afflicted with skin allergies, dogs will constantly lick and scratch at the affected areas in attempts to soothe the itching. If left untreated, the excess moisture from the dog’s saliva and constant trauma to the area will lead to infections called hot spots. The three main culprits causing the itching are flea allergic dermatitis (FAD), cutaneous adverse food reactions (CAFR), and canine atopic dermatitis (AD). Figuring out the exact type of dermatitis can be difficult because many skin diseases exhibit nearly identical clinical signs: itchy, dry, and inflamed skin. These diseases are often accompanied by secondary bacterial infections, which adds another layer of difficulty to the diagnosis. Fortunately, FAD, CAFR, and AD tend to occur more frequently and affect the skin in predictable patterns, which helps veterinarians narrow down and eliminate other potential diseases. Due to the confounding nature of their symptoms, FAD and CAFR must be ruled out first before AD can be confirmed.

FAD is quite simple to diagnose because it manifests in predictable areas of the body. Veterinary researcher Petr Fisara describes FAD as “a common skin disease of dogs in which affected individuals experience a hypersensitivity response induced by salivary antigens that are injected intradermally during flea feeding” (1). To put it plainly, the flea’s mechanism of blood-feeding involves injecting the skin with saliva that contains antigens and proteins. These salivary antigens and proteins are recognized as foreign by the dog’s immune system, triggering an inflammatory response and making the animal itchy. Since the dog is allergic to the flea’s saliva, it may be itchy even if no fleas are physically present. French veterinary dermatologist Catherine Laffort-Dassot ran a study in 2004 on FAD and found that “fleas were observed in only 65% of flea-allergic dogs. In 15% of these cases, neither fleas nor flea faeces were found” (2). FAD has similar clinical signs to other skin conditions and can occur in the absence of fleas; however, another key characteristic of this disease may aid in the diagnosis.

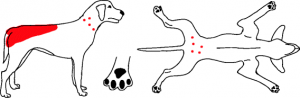

Figure 1. Common areas affected by FAD. Courtesy Hensel et al. 2015

Figure 1. Common areas affected by FAD. Courtesy Hensel et al. 2015

When fleas are not directly found on the patient, the location of skin irritation is the primary indicator of FAD. In the same study, Laffort-Dassot found that irritated skin usually appears around the dog’s lower back near the tail base and the rear legs near its belly, as shown in figure 1 (2). Once FAD is confirmed, the treatment aims to eliminate the source of the saliva by killing the fleas. Usually, over-the-counter topical flea products are not as effective, but veterinarians are able to prescribe oral medications that provide much better flea control. Itchiness that is resolved after flea products are used suggests a FAD diagnosis. In certain areas, such as California, fleas are endemic year-round so owners must be diligent in using flea control to ensure their dog stays itch-free.

CAFR affects different areas on the body than FAD does so it can be tested for at the same time. Swiss veterinarian Frederic Gachen describes CAFR as “reactions to an otherwise harmless dietary component, which are experienced by certain individuals upon ingestion” (3). Proteins are the usual suspects of these allergic reactions. The exact mechanism of CAFR is unknown, but the human variant involves the immune system identifying food antigens, usually in the form of peptides, as foreign (4). This immune response leads to the allergic symptoms commonly associated with food allergies. In dogs, itchiness of the paws and the ears are most commonly associated with CAFR, but other areas such as the muzzle may be affected as well.

Figure 2. Common areas affected by CAFR and AD. Courtesy Hensel et al. 2015

Figure 2. Common areas affected by CAFR and AD. Courtesy Hensel et al. 2015

The diagnosis of CAFR requires rigorous collaboration between owner and veterinarian to achieve accurate results. An eight-week diet elimination trial is used to determine what protein sources are responsible for the allergic response. The trial involves feeding a diet composed of a different protein source than what is currently eaten. The dog is then reevaluated to see if there was an improvement in clinical signs. For example, if the dog is currently on a beef-based diet, the dog’s diet would not be changed to bison since its amino acid profile is very similar to beef, increasing chances of a cross-reaction. Common protein sources used in elimination trials are rabbit, kangaroo, or fish-based feeds since their protein compositions are quite different from the more traditional ones like beef or chicken. During the trial period, the dog should not be fed anything other than the prescribed diet. If the itching persists after the food trial, another trial must be run using a different protein source. There is no perfect protein source to use for an elimination trial, which complicates CAFR’s diagnosis. Once FAD and CAFR are ruled out and the dog still exhibits signs of itchiness, then AD is the likely culprit.

AD is a skin allergy that causes itchiness due to either environmental or non-environmental allergens. Some common environmental allergens are molds or dust mites, whereas non-environmental allergens can be found in food or flea saliva (5). For example, an FAD reaction found on the tail base can also trigger an AD reaction and cause itching on the belly or feet as well. AD is the toughest of the three types to diagnose because its symptoms are virtually identical to other skin diseases. As a result, AD necessitates a diagnosis of exclusion. Only when other possible skin allergies are ruled out can AD be confirmed. AD can manifest on the belly, feet, and ears, similar to CAFR shown in figure 2. Treatment of environmental AD is less straightforward when compared to FAD or CAFR because it is difficult to avoid the offending antigens. Completely eliminating pollen from the air or dust from one’s home is both difficult and unrealistic. There is no cure for AD, so treatment is aimed at reducing itchiness using medications and shampoos. If the general practitioner is unable to control the dog’s itch using the symptomatic approach, veterinary dermatologists have more elaborate methods. They can run allergy tests, which may reveal the exact allergens causing the itchiness. The dermatologist then injects the dog with low doses of those allergens to train its immune system in a manner similar to flu vaccines. Once injected, the body recognizes the weakened allergen and fights it off, creating a memory of this allergen in the immune system. When the dog is exposed to the normal allergen, the immune system is already primed, reducing the severity of the itchiness. AD is the most difficult of the three allergies to diagnose, but treatment is usually effective.

The three most common skin allergies in dogs are FAD, CAFR, and AD. FAD is controlled by eliminating the fleas using oral medications, CAFR is controlled by feeding the animal a novel protein diet, and AD is controlled with antipruritic medication. These allergies cannot be cured, so treatment is aimed at reducing exposure to the offending antigens and alleviating any secondary problems through proper maintenance of symptoms. Although initial clinical signs may appear mild, they have the potential to become severe if left untreated. Skin allergies in dogs can be tricky to diagnose and current treatment methods are not entirely perfect; however, the impacts of allergies can be mitigated through increased diligence and the development of a strong veterinarian-owner relationship.

References

- Fisara P. Shipstone M. von Berky A. von Berky J. 2015. A small-scale open-label study of the treatment of canine flea allergy dermatitis with fluralaner. Vet Dermatol. 26(6): 417-420. DOI:10.1111/vde.12249.

- Laffort-Dassot C. Carlotti DN. Pin D. Jasmin P. 2004. Diagnosis of flea allergy dermatitis: comparison of intradermal testing with flea allergens and a FcepsilonRI alpha-based IgE assay in response to flea control. Vet Dermatol. 15(5):321-30. DOI: 10.1111/j.1365-3164.2004.00394.x.

- Gaschen FP. Merchant SR. 2011. Adverse Food Reactions in Dogs and Cats. Vet Clin N Am-Small. 41(2): 361-379. DOI: 10.1016/j.cvsm.2011.02.005.

- Pali-Schöl I. De Lucia M. Jackson H. Janda J. Mueller RS. Jensen-Jarolim E. 2017. Comparing immediate-type food allergy in humans and companion animals– revealing unmet needs. Allergy. 72(11): 1643- 1656. DOI: 10.1111/all.13179.

- Hensel P. Santoro D. Favrot C. Hill P. Griffin C. 2015. Canine atopic dermatitis: detailed guidelines for diagnosis and allergen identification. BMC Vet Res. 11:196. DOI: 10.1186/s12917-015-0515-5.